Moby Dick; Or, The Whale

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale Moby Dick

Moby Dick Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener

Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition)

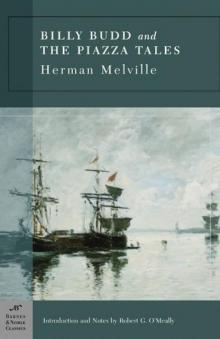

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition) Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales

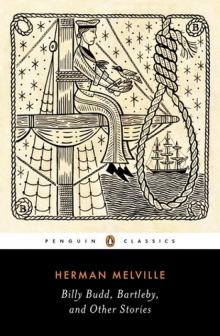

Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories

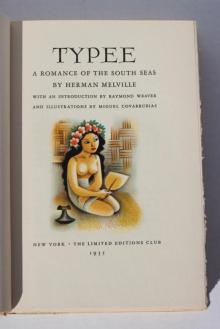

Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories Typee: A Romance of the South Seas

Typee: A Romance of the South Seas Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas

Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War Redburn. His First Voyage

Redburn. His First Voyage Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II

Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II Typee

Typee The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids

The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids Herman Melville- Complete Poems

Herman Melville- Complete Poems Bartleby and Benito Cereno

Bartleby and Benito Cereno Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Mardi and a Voyage Thither

Mardi and a Voyage Thither The Confidence-Man

The Confidence-Man Billy Budd and Other Stories

Billy Budd and Other Stories Bartleby the Scrivener

Bartleby the Scrivener Typee: A Romance of the South Sea

Typee: A Romance of the South Sea I and My Chimney

I and My Chimney Billy Budd

Billy Budd Pierre, Or the Ambiguities

Pierre, Or the Ambiguities Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street

Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street Four Great American Classics

Four Great American Classics White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War The Piazza Tales

The Piazza Tales Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile

Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile