- Home

- Herman Melville

Billy Budd and Other Stories

Billy Budd and Other Stories Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction

Bartleby

The Piazza

The Encantadas or Enchanted Isles

The Bell-Tower

Benito Cereno

The Paradise Of Bachelors And The Tartarus of Maids

Billy Budd, Sailor - (An inside narrative)

FOR THE BEST IN PAPERBACKS, LOOK FOR THE

CLICK ON A CLASSIC

Read more Herman Melville in Penguin Classics

FOR THE BEST IN CLASSIC LITERATURE LOOK FOR THE

PENGUINCLASSICS

BILLY BUDD, SAILOR AND OTHER STORIES

HERMAN MELVILLE was born on August 1, 1819, in New York City, the son of a merchant. Only twelve when his father died bankrupt, young Herman tried work as a bank clerk, as a cabin-boy on a trip to Liverpool, and as an elementary schoolteacher, before shipping in January 1841 on the whaler Acushnet, bound for the Pacific. Deserting ship the following year in the Marquesas, he made his way to Tahiti and Honolulu, returning as ordinary seaman on the frigate United States to Boston, where he was discharged in October 1844. Books based on these adventures won him immediate success. By 1850 he was married, had acquired a farm near Pittsfield, Massachusetts (where he was the impetuous friend and neighbor of Nathaniel Hawthorne), and was hard at work on his masterpiece Moby-Dick. But literary success soon faded; his complexity increasingly alienated readers. After a visit to the Holy Land in January 1857, he turned from writing prose fiction to poetry. In 1863, during the Civil War, he moved back to New York City, where from 1866 to 1885 he was a deputy inspector in the Custom House, and where, on September 28, 1891, he died. A draft of a final prose work, Billy Budd, Sailor, was left unfinished and uncollated; packed tidily away by his widow, it was not rediscovered and published until 1924.

FREDERICK BUSCH is the author of many works of fiction, including the novels Rounds, Take This Man, The Mutual Friend, and Invisible Writing. He teaches literature and fiction writing at Colgate University.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi - -110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank,

Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

This edition edited and with an introduction by Frederick Busch first published in the United States of America in Penguin Classics, 1986 Simultaneously published in Canada

Introduction copyright © Viking Penguin Inc., 1986

All rights reserved

Billy Budd, Sailor (An inside narrative) is the Reading Text as edited from

a genetic study of the manuscript by Harrison Hayford and Merton M.

Sealts, Jr., here

eISBN : 978-1-101-07586-9

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any

other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by

law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate

in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of

the author’s rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

Introduction

When he was thirty-three he felt finished. The book he knew to be speciat—it “is of the horrible texture of a fabric that should be woven of ships’ cables & hawsers,” he wrote. “A Polar wind blows through it, & birds of prey hover over it”—had failed. American and English reviewers had roasted Moby-Dick (1851), and in eighteen months the American edition sold 2,300 copies. Pierre (1852) sold 2,030 copies over thirty-five years, earning Melville the scorn of reviewers—they questioned his sanity as well as his skill—and, by the end of his life, a total of $157.

He had to worry about money, for he farmed a little but counted on the harvest of his writing, and his wife’s small trust fund, for the support of their family. This support was threatened, and since money is a letter from the world to an author about his work, Melville had to face up to the prospect of not getting across his doubting dark vision; for he received too little of the mail that would have assured him that he was heard. As he had complained in a letter to Hawthorne in 1851: “Dollars damn me; and the malicious Devil is forever grinning in upon me, holding the door ajar.... I shall be worn out and perish, like an old nutmeg grater, grated to pieces by the constant attrition of the wood, that is, the nutmeg. What I feel most moved to write, that is banned—it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the otber way I cannot. So the product is a final hash, and all my books are botches.”

The well-received author of travel and adventure stories such as Typee (1846) and Mardi (1849) had become the student of Shakespeare’s and Carlyle’s works, the hard questioner of heavenly works, and the man whose soul had resonated in response to the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne—“there is the blackness of darkness beyond,” he wrote of Hawthorne’s tales, and he praised “those short, quick probings at the very axis of reality,” which had “dropped germinous seeds into my soul.” Melville had lost what ease he’d possessed, and now his work, too, would lose its ease. Into Moby-Dick, which he was writing as he wrote to Hawthorne, he put “the sane madness of vital truth,” and the world didn’t want to hear it.

And so we come to the exhausted Melville of 1852. He begins to speak—it is nearly impossible, still, for him to be silent—of what obsesses him: the failure of crucial messages to get through. That matter becomes central; those messages are the mail of which I speak.

It is likely that Melville had come to love Hawthorne: the handsome older writer, Melville wrote in “Hawthorne and His Mosses” in 1850, “shoots his strong... roots into the hot soil of my ... soul.” They were neighbors and saw one another, though less than Melville wished, and then Hawthorne moved away; they corresponded, exchanging books (Pierre for The Blithedale Romance) and ideas. The case of Agatha Hatch Robertson was relayed by Melville. It involved a young wife who waited seventeen years for word—literally, for mail—from her husband, who had left to seek work. Melville here postulates to Hawthorne how the story of Agatha and her mailbox might be told: “As her hopes gradually decay in her, so does the post itself & the little box decay. The post rots in the ground at last. Owing to its being little used— hardly used at all—grass grows rankly about it. At last a little bird nests in it. At last the post falls.” (My italics.)

It seems clear that this synopsis speaks for Melville. The story of abandonment and apprehensive waiting for messages is relevant to a writer in Melville’s situation—he laments the undelivered incoming mail (the world’s attention) and the outgoing mail (his writing) that does not get through. The nesting bird underscores not only the pathos of the disuse of the mailbox, but Melville’s sense of his ridiculousness: is he merely a white-stained post? And liste

n to the rhythm of the repetition of “at last” and “At last” and “At last”: it is incantatory, funereal, and about Herman Melville’s fatigue.

Melville had steeped himself in Shakespeare’s tragedies as he prepared to write Moby-Dick. In “Mosses,” he had said, “Through the mouths of the dark characters of Hamlet, Timon, Lear, and Iago, he [Shakespeare] craftily says, or sometimes insinuates, the things which we feel to be so terrifically true that it were all but madness for any good man, in his own proper character, to utter or even hint of them.” Whenever he wrote of literature, Melville tended to write about the process of writing in general, and his own in particular; he does so above, homing in on his own relationship to Ahab, who—like Pierre—served as Melville’s dark mask. Now he ventriloquized from within his notion of Agatha, and later he would use Claggart and Captain Vere.

It is Hamlet who speaks in the outline of the Agatha story. Grass grows “rankly” around the rotting post; it is Hamlet who, lamenting religious injunctions against suicide, describing life as weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable, bemoaning the need for silence (“I must hold my tongue”); it is Hamlet who calls the world “an unweeded garden” taken over by things rank and gross.” (My italics.) Melville was low enough in spirit to place himself in Hamlet’s garden, and in Agatha’s dooryard.

In October 1852, Putnam’s magazine invited him to contribute work. In December, he began to write the Agatha story. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t complete it, for he had said its essential elements to Hawthorne; and it was Agatha’s situation, not self, that was dark and alive to Melville. She was his emblem more than his story. But he did work at silence and undelivered messages that year, and did give Putnam’s the tale of Bartleby, published in 1853.

The mask through which Melville speaks in the story is that of a decent, pragmatic, elderly Wall Street lawyer (who practices not far from Melville’s boyhood neighborhood, and the Custom-House from which he retired in 1885). The narrator is proud to work for robber-barons and is as different from the copyist, or scrivener, Bartleby, as seems possible. And yet, like Bartleby, he is a victim of politics: as he has lost work as Master of Chancery because administrations changed, so Bartleby has lost a position, we learn, for similar reasons. Bartleby comes to haunt the lawyer and his chambers; Turkey and Nippers, matching opposites—one law clerk is torpid when the other is drunkenly inflamed, and vice versa—strike the motif of doubleness for the story, and it soon becomes clear that something in these opposites, the narrator and his scrivener, is also matched.

For against all wisdom, not to mention sound business practices, Bartleby is kept on, in spite of his refusal to work (“I would prefer not to”), as if the narrator required his presence. It seems that just as Melville finds his mask in the narrator—it is at this time that a campaign of family and friends fails to yield Melville a diplomatic appointment by officials in the new administration of President Franklin Pierce—so the narrator finds his darker self in Bartleby. Quite like Bartleby, who ends up dead, “his face towards a high wall,” the narrator has chambers (on Wall Street) that “looked upon the white wall of the interior of a spacious sky-light shaft” at one end, and, at the other, upon “a lofty brick wall.” Like Bartleby (who is described, once, as “my fate”), he is in a blind alley of his life, and he looks upon “dead” walls.

In some ways, then, Melville writes not only of existential traps, but of the need to cope with or create or accede to the presence of metaphors of one’s interior being. He is speaking of aspects of the consciousness that makes fiction—the creation of alternate, mirroring selves—and it is selfish, needful, cunning, self-pitying, and sometimes even generous.

Bartleby, who starved away from an intolerable world—perhaps on behalf of the narrator who had digested too much of it—had been a clerk “in the Dead Letter Office in Washington.” The narrator, lamenting Bartleby and humanity, but probably also Herman Melville, speculates on “Dead letters! Does it not sound like dead men?” He considers what dead letters might carry—pardon, hope, good tidings—and concludes that “On errands of life, these letters speed to death.” For life, also read fiction.

Published by Harper Brothers into the mid-1850s, Melville also read Harper’s magazine, renewing his subscription in 1852. And it was in Harper’s that Charles Dickens’s Bleak House was published serially in America, from April 1852 to October 1853. There’s little reason to doubt that Melville saw those issues, including the issues of June and July 1852, containing the chapters (X and XI) called “The Law-Writer” and “Our Dear Brother.” In them, a man is shown to be very much about paper and pen and, like Bartleby (at one point described as “folded up like a huge folio”), is a parody of Melville’s profession.

The law copyist, or scrivener, lives in Cook’s Court, near Chancery Lane. (Remember that Bartleby’s employer was Master of Chancery and that, well into the mid-twentieth century, New York’s Wall Street was the equivalent of London’s Inns of Court.) The man who copies legal documents in Bleak House, Melville would have read, calls himself “Nemo, Latin for no one.” An advantage cited about Nemo is “that he never wants to sleep”; he is a haunted man. His landlady says, “They say he has sold himself to the Enemy,” the Devil; he is “black-humored and gloomy” and lives in a tiny room “nearly black with soot, and grease, and dirt”; his desk is “a wilderness marked with a rain of ink.” “No curtain veils the darkness of the night,” but Nemo’s shutters are drawn; “through the two gaunt holes pierced in them, famine might be staring in....” The filthy, ragged copyist, a figure of total despair, lies dead in his squalid room, the victim of an overdose of opium.

Melville, I suggest, read about Nemo before he wrote his story of Wall Street. He made Nemo his own, though he was drawn to him, I think, because the combination of despair, cruel laws, alienation, copying-out, and that “rain of ink” were irresistible. Bartleby turns his face to a dead wall because he cannot tolerate his life. In the Dickens, it is a broken heart, a lost history, a condition in life that is denied by the scrivener. In the Melville, it is human life itself that is denied. Dickens, when he drew his copyist in Bleak House, was angry at conditions in English life; Melville, under Dickens’s influence, saw his soul as “grated to pieces” by the great chore of living.

The Encantadas or Enchanted Isles, published in Putnam’s in 1854, appeals to the contemporary sensibility as much as Bartleby or Benito Cereno. Although these are long stories, or novellas, they are written for magazine publication and are necessarily concise. The energy that comes of such compression, coupled with Melville’s darkening vision and sexual and economic desperation—a third child was born in 1853, a fourth in 1855-results in a fiction that is grim (or effortfully funny, like “The Happy Failure” or “I and My Chimney,” also published in 1854), a fiction that appropriates wild symbology from the romance (for example, a tortoise on the back of which is emblazoned a memento mori), and the mythic, fablelike qualities one associates with certain contemporary writers.

The Encantadas are the Galapagos Islands, “cinders dumped here and there in an outside city lot,” Melville calls them. They are described as a wasteland in the seas, where natural life is cruel and human life that drifts in even crueller. Instead of chapters, we have ten sketches; there is no central character, and no single story. The islands become a repository for attitude and mood. They are metaphors that link Melville’s somber music, which describes an island as “tumbled masses of blackish or greenish stuff like the dross of an iron-furnace,” yielding “a most Plutonian sight.” This is a suite about hell, the outer, physical hell that is analogue to a sad man’s interior hell—that, say, of the man who had, in discussing Moby-Dick, mentioned “the hell-fire in which the whole book is broiled.” These sketches, from the former travel and adventure writer, offer a Swiftian scorning song about men who are more like dogs, and about islands that are more like ideas. If there is anyone heroic or admirable, it is Hunilla, of “Sketch Eighth,” who, abandoned on an island, endure

s her husband’s and brother’s death, and years of torture, to be seen, at the story’s end, riding “upon a small gray ass ...” and eyeing “the jointed workings of the beast’s armorial cross.” When Melville, the unbeliever, finds a character heroic, he finds that character Christlike, or at least crucified—Billy Budd, for example, and Ahab.

It is noteworthy that in describing an apocalyptically ugly wilderness like the Encantadas, Melville called them “cinders” and described them as a waste product of industry. Like all sensitive men and women of his time, and as a former sailor and a farmer, he was aware of the cruel encroachments of industrial process upon the countryside. His Harper’s story of 1855, “The Tartarus of Maids,” is often read as an attack upon nineteenth-century industrial despoliations. It is that, surely. But it is equally concerned with sexuality, and with fiction, and is as much about isolation and long silence as The Encantadas.

The stories of this period, when examined in their collections, The Piazza Tales (1856), abound in vertical images, phallic shapes—lightning rods, masts, chimneys, and the high building that houses “The Paradise of Bachelors” in the story that was published along with “The Tartarus of Maids.” As characters in Bartleby were paired, the two stories here are paired, the Pickwickian “Bachelors,” the Dantean “Maids.” The number nine—does Melville think of the Ninth Circle of Hell?—is echoed in each: nine carefree bachelors dine, and paper production in “Maids” takes nine minutes. We might remember that the nine months of gestation would be significant to Melville as well around this time.

So, in “Bachelors,” the men dine at the top of a high building in London. They eat and drink in great quantity, are courtly to one another, and are “a band of brothers,” with “no wives or children to give an anxious thought.” Melville is stating his dream of freedom from the domestic responsibilities that stalk him (and which he cannot easily meet); he also expresses his desire to be free of the sexuality that, as his fiction demonstrates, he copes with uneasily: it is Apollonian youth or bachelor brothers, who most please the narrators who speak for him. Here, the men take snuff together from a silver goat’s horn; they remove the snuff, which they will stuff into themselves, by “inserting ... thumb and forefinger into its mouth.” Melville goes to some length to create images that have to do with orifices and infantile pleasure. The bachelors are boys, and their aim is self-gratification, which exists in opposition to the cycles of biology represented in “The Tartarus of Maids,” another Melville tale of the underworld.

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale Moby Dick

Moby Dick Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener

Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition)

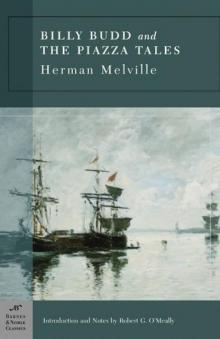

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition) Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales

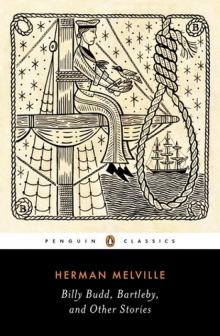

Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories

Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories Typee: A Romance of the South Seas

Typee: A Romance of the South Seas Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas

Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War Redburn. His First Voyage

Redburn. His First Voyage Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II

Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II Typee

Typee The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids

The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids Herman Melville- Complete Poems

Herman Melville- Complete Poems Bartleby and Benito Cereno

Bartleby and Benito Cereno Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Mardi and a Voyage Thither

Mardi and a Voyage Thither The Confidence-Man

The Confidence-Man Billy Budd and Other Stories

Billy Budd and Other Stories Bartleby the Scrivener

Bartleby the Scrivener Typee: A Romance of the South Sea

Typee: A Romance of the South Sea I and My Chimney

I and My Chimney Billy Budd

Billy Budd Pierre, Or the Ambiguities

Pierre, Or the Ambiguities Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street

Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street Four Great American Classics

Four Great American Classics White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War The Piazza Tales

The Piazza Tales Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile

Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile