- Home

- Herman Melville

Mardi and a Voyage Thither

Mardi and a Voyage Thither Read online

Mardi and a Voyage Thither

Herman Melville

An ambitious and far reaching allegorical voyage which, though not exactly a success, was Melville's first attempt at a book on the scale of Moby-Dick. Here is a passage which is reflective of the style, and outlook, of Mardi:

So, if after all these fearful, fainting traces, the verdict be, the golden haven was not gained;-yet in bold quest thereof, better to sink in boundless deeps, than float on vulgar shoals: and give me, ye gods, an utter wreck, if wreck I do.-Herman Melville

VOL. I

PREFACE

Not long ago, having published two narratives of voyages in the Pacific, which, in many quarters, were received with incredulity, the thought occurred to me, of indeed writing a romance of Polynesian adventure, and publishing it as such; to see whether, the fiction might not, possibly, be received for a verity: in some degree the reverse of my previous experience.

This thought was the germ of others, which have resulted in Mardi.

New York, January, 1849.

CHAPTER I

Foot In Stirrup

We are off! The courses and topsails are set: the coral-hung anchor swings from the bow: and together, the three royals are given to the breeze, that follows us out to sea like the baying of a hound. Out spreads the canvas-alow, aloft-boom-stretched, on both sides, with many a stun' sail; till like a hawk, with pinions poised, we shadow the sea with our sails, and reelingly cleave the brine.

But whence, and whither wend ye, mariners?

We sail from Ravavai, an isle in the sea, not very far northward from the tropic of Capricorn, nor very far westward from Pitcairn's island, where the mutineers of the Bounty settled. At Ravavai I had stepped ashore some few months previous; and now was embarked on a cruise for the whale, whose brain enlightens the world.

And from Ravavai we sail for the Gallipagos, otherwise called the Enchanted Islands, by reason of the many wild currents and eddies there met.

Now, round about those isles, which Dampier once trod, where the Spanish bucaniers once hived their gold moidores, the Cachalot, or sperm whale, at certain seasons abounds.

But thither, from Ravavai, your craft may not fly, as flies the sea-gull, straight to her nest. For, owing to the prevalence of the trade winds, ships bound to the northeast from the vicinity of Ravavai are fain to take something of a circuit; a few thousand miles or so. First, in pursuit of the variable winds, they make all haste to the south; and there, at length picking up a stray breeze, they stand for the main: then, making their easting, up helm, and away down the coast, toward the Line.

This round-about way did the Arcturion take; and in all conscience a weary one it was. Never before had the ocean appeared so monotonous; thank fate, never since.

But bravo! in two weeks' time, an event. Out of the gray of the morning, and right ahead, as we sailed along, a dark object rose out of the sea; standing dimly before us, mists wreathing and curling aloft, and creamy breakers frothing round its base.-We turned aside, and, at length, when day dawned, passed Massafuero. With a glass, we spied two or three hermit goats winding down to the sea, in a ravine; and presently, a signal: a tattered flag upon a summit beyond.

Well knowing, however, that there was nobody on the island but two or three noose-fulls of runaway convicts from Chili, our captain had no mind to comply with their invitation to land. Though, haply, he may have erred in not sending a boat off with his card.

A few days more and we "took the trades." Like favors snappishly conferred, they came to us, as is often the case, in a very sharp squall; the shock of which carried away one of our spars; also our fat old cook off his legs; depositing him plump in the scuppers to leeward.

In good time making the desired longitude upon the equator, a few leagues west of the Gallipagos, we spent several weeks chassezing across the Line, to and fro, in unavailing search for our prey. For some of their hunters believe, that whales, like the silver ore in Peru, run in veins through the ocean. So, day after day, daily; and week after week, weekly, we traversed the self-same longitudinal intersection of the self-same Line; till we were almost ready to swear that we felt the ship strike every time her keel crossed that imaginary locality.

At length, dead before the equatorial breeze, we threaded our way straight along the very Line itself. Westward sailing; peering right, and peering left, but seeing naught.

It was during this weary time, that I experienced the first symptoms of that bitter impatience of our monotonous craft, which ultimately led to the adventures herein recounted.

But hold you! Not a word against that rare old ship, nor its crew.

The sailors were good fellows all, the half, score of pagans we had shipped at the islands included. Nevertheless, they were not precisely to my mind. There was no soul a magnet to mine; none with whom to mingle sympathies; save in deploring the calms with which we were now and then overtaken; or in hailing the breeze when it came.

Under other and livelier auspices the tarry knaves might have developed qualities more attractive. Had we sprung a leak, been «stove» by a whale, or been blessed with some despot of a captain against whom to stir up some spirited revolt, these shipmates of mine might have proved limber lads, and men of mettle. But as it was, there was naught to strike fire from their steel.

There were other things, also, tending to make my lot on ship-board very hard to be borne. True, the skipper himself was a trump; stood upon no quarter-deck dignity; and had a tongue for a sailor. Let me do him justice, furthermore: he took a sort of fancy for me in particular; was sociable, nay, loquacious, when I happened to stand at the helm. But what of that? Could he talk sentiment or philosophy?

Not a bit. His library was eight inches by four: Bowditch, and Hamilton Moore.

And what to me, thus pining for some one who could page me a quotation from Burton on Blue Devils; what to me, indeed, were flat repetitions of long-drawn yams, and the everlasting stanzas of Black-eyed Susan sung by our full forecastle choir? Staler than stale ale.

Ay, ay, Arcturion! I say it in no malice, but thou wast exceedingly dull. Not only at sailing: hard though it was, that I could have borne; but in every other respect. The days went slowly round and round, endless and uneventful as cycles in space. Time, and timepieces; How many centuries did my hammock tell, as pendulum-like it swung to the ship's dull roll, and ticked the hours and ages. Sacred forever be the Areturion's fore-hatch-alas! sea-moss is over it now-and rusty forever the bolts that held together that old sea hearth-stone, about which we so often lounged. Nevertheless, ye lost and leaden hours, I will rail at ye while life lasts.

Well: weeks, chronologically speaking, went by. Bill Marvel's stories were told over and over again, till the beginning and end dovetailed into each other, and were united for aye. Ned Ballad's songs were sung till the echoes lurked in the very tops, and nested in the bunts of the sails. My poor patience was clean gone.

But, at last after some time sailing due westward we quitted the Line in high disgust; having seen there, no sign of a whale.

But whither now? To the broiling coast of Papua? That region of sunstrokes, typhoons, and bitter pulls after whales unattainable. Far worse. We were going, it seemed, to illustrate the Whistonian theory concerning the damned and the comets;-hurried from equinoctial heats to arctic frosts. To be short, with the true fickleness of his tribe, our skipper had abandoned all thought of the Cachalot. In desperation, he was bent upon bobbing for the Right whale on the Nor'-West Coast and in the Bay of Kamschatska.

To the uninitiated in the business of whaling, my feelings at this juncture may perhaps be hard to understand. But this much let me say: that Right whaling on the Nor'-West Coast, in chill and dismal fogs,

the sullen inert monsters rafting the sea all round like Hartz forest logs on the Rhine, and submitting to the harpoon like half-stunned bullocks to the knife; this horrid and indecent Right whaling, I say, compared to a spirited hunt for the gentlemanly Cachalot in southern and more genial seas, is as the butchery of white bears upon blank Greenland icebergs to zebra hunting in Caffraria, where the lively quarry bounds before you through leafy glades.

Now, this most unforeseen determination on the part of my captain to measure the arctic circle was nothing more nor less than a tacit contravention of the agreement between us. That agreement needs not to be detailed. And having shipped but for a single cruise, I had embarked aboard his craft as one might put foot in stirrup for a day's following of the hounds. And here, Heaven help me, he was going to carry me off to the Pole! And on such a vile errand too! For there was something degrading in it. Your true whaleman glories in keeping his harpoon unspotted by blood of aught but Cachalot. By my halidome, it touched the knighthood of a tar. Sperm and spermaceti! It was unendurable.

"Captain," said I, touching my sombrero to him as I stood at the wheel one day, "It's very hard to carry me off this way to purgatory.

I shipped to go elsewhere."

"Yes, and so did I," was his reply. "But it can't be helped. Sperm whales are not to be had. We've been out now three years, and something or other must be got; for the ship is hungry for oil, and her hold a gulf to look into. But cheer up my boy; once in the Bay of Kamschatka, and we'll be all afloat with what we want, though it be none of the best."

Worse and worse! The oleaginous prospect extended into an immensity of Macassar. "Sir," said I, "I did not ship for it; put me ashore somewhere, I beseech." He stared, but no answer vouchsafed; and for a moment I thought I had roused the domineering spirit of the sea-captain, to the prejudice of the more kindly nature of the man.

But not so. Taking three turns on the deck, he placed his hand on the wheel, and said, "Right or wrong, my lad, go with us you must.

Putting you ashore is now out of the question. I make no port till this ship is full to the combings of her hatchways. However, you may leave her if you can." And so saying he entered his cabin, like Julius Caesar into his tent.

He may have meant little by it, but that last sentence rung in my ear like a bravado. It savored of the turnkey's compliments to the prisoner in Newgate, when he shoots to the bolt on him.

"Leave the ship if I can!" Leave the ship when neither sail nor shore was in sight! Ay, my fine captain, stranger things have been done.

For on board that very craft, the old Arcturion, were four tall fellows, whom two years previous our skipper himself had picked up in an open boat, far from the farthest shoal. To be sure, they spun a long yarn about being the only survivors of an Indiaman burnt down to the water's edge. But who credited their tale? Like many others, they were keepers of a secret: had doubtless contracted a disgust for some ugly craft still afloat and hearty, and stolen away from her, off soundings. Among seamen in the Pacific such adventures not seldom occur. Nor are they accounted great wonders. They are but incidents, not events, in the career of the brethren of the order of South Sea rovers. For what matters it, though hundreds of miles from land, if a good whale-boat be under foot, the Trades behind, and mild, warm seas before? And herein lies the difference between the Atlantic and Pacific:-that once within the Tropics, the bold sailor who has a mind to quit his ship round Cape Horn, waits not for port. He regards that ocean as one mighty harbor.

Nevertheless, the enterprise hinted at was no light one; and I resolved to weigh well the chances. It's worth noticing, this way we all have of pondering for ourselves the enterprise, which, for others, we hold a bagatelle.

My first thoughts were of the boat to be obtained, and the right or wrong of abstracting it, under the circumstances. But to split no hairs on this point, let me say, that were I placed in the same situation again, I would repeat the thing I did then. The captain well knew that he was going to detain me unlawfully: against our agreement; and it was he himself who threw out the very hint, which I merely adopted, with many thanks to him.

In some such willful mood as this, I went aloft one day, to stand my allotted two hours at the mast-head. It was toward the close of a day, serene and beautiful. There I stood, high upon the mast, and away, away, illimitably rolled the ocean beneath. Where we then were was perhaps the most unfrequented and least known portion of these seas. Westward, however, lay numerous groups of islands, loosely laid down upon the charts, and invested with all the charms of dream-land.

But soon these regions would be past; the mild equatorial breeze exchanged for cold, fierce squalls, and all the horrors of northern voyaging.

I cast my eyes downward to the brown planks of the dull, plodding ship, silent from stem to stern; then abroad.

In the distance what visions were spread! The entire western horizon high piled with gold and crimson clouds; airy arches, domes, and minarets; as if the yellow, Moorish sun were setting behind some vast Alhambra. Vistas seemed leading to worlds beyond. To and fro, and all over the towers of this Nineveh in the sky, flew troops of birds.

Watching them long, one crossed my sight, flew through a low arch, and was lost to view. My spirit must have sailed in with it; for directly, as in a trance, came upon me the cadence of mild billows laving a beach of shells, the waving of boughs, and the voices of maidens, and the lulled beatings of my own dissolved heart, all blended together.

Now, all this, to be plain, was but one of the many visions one has up aloft. But coming upon me at this time, it wrought upon me so, that thenceforth my desire to quit the Arcturion became little short of a frenzy.

CHAPTER II

A Calm

Next day there was a calm, which added not a little to my impatience of the ship. And, furthermore, by certain nameless associations revived in me my old impressions upon first witnessing as a landsman this phenomenon of the sea. Those impressions may merit a page.

To a landsman a calm is no joke. It not only revolutionizes his abdomen, but unsettles his mind; tempts him to recant his belief in the eternal fitness of things; in short, almost makes an infidel of him.

At first he is taken by surprise, never having dreamt of a state of existence where existence itself seems suspended. He shakes himself in his coat, to see whether it be empty or no. He closes his eyes, to test the reality of the glassy expanse. He fetches a deep breath, by way of experiment, and for the sake of witnessing the effect. If a reader of books, Priestley on Necessity occurs to him; and he believes in that old Sir Anthony Absolute to the very last chapter.

His faith in Malte Brun, however, begins to fail; for the geography, which from boyhood he had implicitly confided in, always assured him, that though expatiating all over the globe, the sea was at least margined by land. That over against America, for example, was Asia.

But it is a calm, and he grows madly skeptical.

To his alarmed fancy, parallels and meridians become emphatically what they are merely designated as being: imaginary lines drawn round the earth's surface.

The log assures him that he is in such a place; but the log is a liar; for no place, nor any thing possessed of a local angularity, is to be lighted upon in the watery waste.

At length horrible doubts overtake him as to the captain's competency to navigate his ship. The ignoramus must have lost his way, and drifted into the outer confines of creation, the region of the everlasting lull, introductory to a positive vacuity.

Thoughts of eternity thicken. He begins to feel anxious concerning his soul.

The stillness of the calm is awful. His voice begins to grow strange and portentous. He feels it in him like something swallowed too big for the esophagus. It keeps up a sort of involuntary interior humming in him, like a live beetle. His cranium is a dome full of reverberations. The hollows of his very bones are as whispering galleries. He is afraid to speak loud, lest he be stunned; like the man in the bass drum.

But more than al

l else is the consciousness of his utter helplessness. Succor or sympathy there is none. Penitence for embarking avails not. The final satisfaction of despairing may not be his with a relish. Vain the idea of idling out the calm. He may sleep if he can, or purposely delude himself into a crazy fancy, that he is merely at leisure. All this he may compass; but he may not lounge; for to lounge is to be idle; to be idle implies an absence of any thing to do; whereas there is a calm to be endured: enough to attend to, Heaven knows.

His physical organization, obviously intended for locomotion, becomes a fixture; for where the calm leaves him, there he remains. Even his undoubted vested rights, comprised in his glorious liberty of volition, become as naught. For of what use? He wills to go: to get away from the calm: as ashore he would avoid the plague. But he can not; and how foolish to revolve expedients. It is more hopeless than a bad marriage in a land where there is no Doctors' Commons. He has taken the ship to wife, for better or for worse, for calm or for gale; and she is not to be shuffled off. With yards akimbo, she says unto him scornfully, as the old beldam said to the little dwarf:-"Help yourself"

And all this, and more than this, is a calm.

CHAPTER III

A King For A Comrade

At the time I now write of, we must have been something more than sixty degrees to the west of the Gallipagos. And having attained a desirable longitude, we were standing northward for our arctic destination: around us one wide sea.

But due west, though distant a thousand miles, stretched north and south an almost endless Archipelago, here and there inhabited, but little known; and mostly unfrequented, even by whalemen, who go almost every where. Beginning at the southerly termination of this great chain, it comprises the islands loosely known as Ellice's group; then, the Kingsmill isles; then, the Radack and Mulgrave clusters. These islands had been represented to me as mostly of coral formation, low and fertile, and abounding in a variety of fruits. The language of the people was said to be very similar to that or the Navigator's islands, from which, their ancestors are supposed to have emigrated.

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale Moby Dick

Moby Dick Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener

Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition)

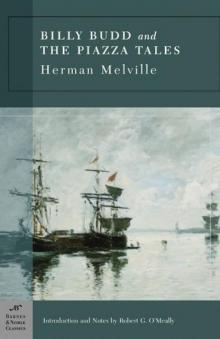

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition) Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales

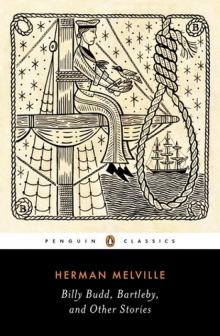

Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories

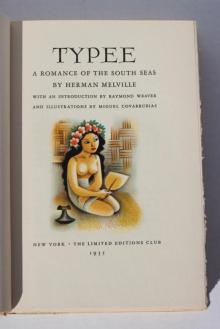

Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories Typee: A Romance of the South Seas

Typee: A Romance of the South Seas Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas

Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War Redburn. His First Voyage

Redburn. His First Voyage Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II

Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II Typee

Typee The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids

The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids Herman Melville- Complete Poems

Herman Melville- Complete Poems Bartleby and Benito Cereno

Bartleby and Benito Cereno Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Mardi and a Voyage Thither

Mardi and a Voyage Thither The Confidence-Man

The Confidence-Man Billy Budd and Other Stories

Billy Budd and Other Stories Bartleby the Scrivener

Bartleby the Scrivener Typee: A Romance of the South Sea

Typee: A Romance of the South Sea I and My Chimney

I and My Chimney Billy Budd

Billy Budd Pierre, Or the Ambiguities

Pierre, Or the Ambiguities Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street

Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street Four Great American Classics

Four Great American Classics White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War The Piazza Tales

The Piazza Tales Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile

Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile