- Home

- Herman Melville

Typee Page 11

Typee Read online

Page 11

CHAPTER IX

The head of the valley--Cautious advance--A path--Fruit--Discovery of two of the natives--Their singular conduct--Approach towards the inhabited parts of the vale--Sensation produced by our appearance--Reception at the house of one of the natives.

How to obtain the fruit which we felt convinced must grow near at hand wasour first thought.

Typee or Happar? A frightful death at the hands of the fiercest ofcannibals, or a kindly reception from a gentler race of savages? Which?But it was too late now to discuss a question which would so soon beanswered.

The part of the valley in which we found ourselves appeared to bealtogether uninhabited. An almost impenetrable thicket extended from sideto side, without presenting a single plant affording the nourishment wehad confidently calculated upon; and with this object, we followed thecourse of the stream, casting quick glances as we proceeded into the thickjungles on either hand.

My companion--to whose solicitations I had yielded in descending into thevalley--now that the step was taken, began to manifest a degree of cautionI had little expected from him. He proposed that in the event of ourfinding an adequate supply of fruit, we should remain in this unfrequentedportion of the valley--where we should run little chance of being surprisedby its occupants, whoever they might be--until sufficiently recruited toresume our journey; when laying in a store of food equal to our wants, wemight easily regain the bay of Nukuheva, after the lapse of a sufficientinterval to ensure the departure of our vessel.

I objected strongly to this proposition, plausible as it was, as thedifficulties of the route would almost be insurmountable, unacquainted aswe were with the general bearings of the country, and I reminded mycompanion of the hardships which we had already encountered in ouruncertain wanderings; in a word, I said that since we had deemed itadvisable to enter the valley, we ought manfully to face the consequences,whatever they might be; the more especially as I was convinced there wasno alternative left us but to fall in with the natives at once, and boldlyrisk the reception they might give us: and that as to myself, I felt thenecessity of rest and shelter, and that until I had obtained them, Ishould be wholly unable to encounter such sufferings as we had latelypassed through. To the justice of these observations Toby somewhatreluctantly assented.

We were surprised that, after moving as far as we had along the valley, wewould still meet with the same impervious thickets; and thinking thatalthough the borders of the stream might be lined for some distance withthem, yet beyond there might be more open ground, I requested Toby to keepa bright look-out upon one side, while I did the same on the other, inorder to discover some opening in the bushes, and especially to watch forthe slightest appearance of a path or anything else that might indicatethe vicinity of the islanders.

What furtive and anxious glances we cast into those dim-looking shades!With what apprehensions we proceeded, ignorant at what moment we might begreeted by the javelin of some ambushed savage! At last my companionpaused, and directed my attention to a narrow opening in the foliage. Westruck into it, and it soon brought us by an indistinctly traced path to acomparatively clear space, at the farther end of which we descried anumber of the trees, the native name of which is "annuee," and which beara most delicious fruit.

What a race! I hobbling over the ground like some decrepid wretch, andToby leaping forward like a greyhound. He quickly cleared one of the treeson which there were two or three of the fruit, but to our chagrin theyproved to be much decayed; the rinds partly opened by the birds, and theirhearts half devoured. However, we quickly despatched them, and no ambrosiacould have been more delicious.

We looked about us uncertain whither to direct our steps, since the pathwe had so far followed appeared to be lost in the open space around us. Atlast we resolved to enter a grove near at hand, and had advanced a fewrods, when, just upon its skirts, I picked up a slender bread-fruit shootperfectly green, and with the tender bark freshly stript from it. It wasslippery with moisture, and appeared as if it had been but that momentthrown aside. I said nothing, but merely held it up to Toby, who startedat this undeniable evidence of the vicinity of the savages.

The plot was now thickening.--A short distance farther lay a little faggotof the same shoots bound together with a strip of bark. Could it have beenthrown down by some solitary native, who, alarmed at seeing us, hadhurried forward to carry the tidings of our approach to hiscountrymen?--Typee or Happar?--But it was too late to recede, so we moved onslowly, my companion in advance casting eager glances under the trees oneither side, until all at once I saw him recoil as if stung by an adder.Sinking on his knee, he waved me off with one hand, while with the otherhe held aside some intervening leaves, and gazed intently at some object.

Disregarding his injunction, I quickly approached him and caught a glimpseof two figures partly hidden by the dense foliage; they were standingclose together, and were perfectly motionless. They must have previouslyperceived us, and withdrawn into the depths of the wood to elude ourobservation.

My mind was at once made up. Dropping my staff, and tearing open thepackage of things we had brought from the ship, I unrolled the cottoncloth, and holding it in one hand, plucked with the other a twig from thebushes beside me, and telling Toby to follow my example, I broke throughthe covert and advanced, waving the branch in token of peace towards theshrinking forms before me.

They were a boy and a girl, slender and graceful, and completely naked,with the exception of a slight girdle of bark, from which depended atopposite points two of the russet leaves of the bread-fruit tree. An armof the boy, half screened from sight by her wild tresses, was thrown aboutthe neck of the girl, while with the other he held one of her hands inhis; and thus they stood together, their heads inclined forward, catchingthe faint noise we made in our progress, and with one foot in advance, asif half inclined to fly from our presence.

As we drew near, their alarm evidently increased. Apprehensive that theymight fly from us altogether, I stopped short and motioned them to advanceand receive the gift I extended towards them, but they would not; I thenuttered a few words of their language with which I was acquainted,scarcely expecting that they would understand me, but to show that we hadnot dropped from the clouds upon them. This appeared to give them a littleconfidence, so I approached nearer, presenting the cloth with one hand,and holding the bough with the other, while they slowly retreated. At lastthey suffered us to approach so near to them that we were enabled to throwthe cotton cloth across their shoulders, giving them to understand that itwas theirs, and by a variety of gestures endeavouring to make themunderstand that we entertained the highest possible regard for them.

The frightened pair now stood still, whilst we endeavoured to make themcomprehend the nature of our wants. In doing this Toby went through with acomplete series of pantomimic illustrations--opening his mouth from ear toear, and thrusting his fingers down his throat, gnashing his teeth androlling his eyes about, till I verily believe the poor creatures took usfor a couple of white cannibals who were about to make a meal of them.When, however, they understood us, they showed no inclination to relieveour wants. At this juncture it began to rain violently, and we motionedthem to lead us to some place of shelter. With this request they appearedwilling to comply, but nothing could evince more strongly the apprehensionwith which they regarded us, than the way in which, whilst walking beforeus, they kept their eyes constantly turned back to watch every movement wemade, and even our very looks.

"Typee or Happar, Toby?" asked I, as we walked after them.

"Of course, Happar," he replied, with a show of confidence which wasintended to disguise his doubts.

"We shall soon know," I exclaimed; and at the same moment I steppedforward towards our guides, and pronouncing the two names interrogatively,and pointing to the lowest part of the valley, endeavoured to come to thepoint at once. They repeated the words after me again and again, butwithout giving any peculiar emphasis to either, so tha

t I was completelyat a loss to understand them; for a couple of wilier young things than weafterwards found them to have been on this particular occasion neverprobably fell in any traveller's way.

More and more curious to ascertain our fate, I now threw together in theform of a question the words "Happar" and "Mortarkee," the latter beingequivalent to the word "good." The two natives interchanged glances ofpeculiar meaning with one another at this, and manifested no littlesurprise; but on the repetition of the question, after some consultationtogether, to the great joy of Toby, they answered in the affirmative. Tobywas now in ecstasies, especially as the young savages continued toreiterate their answer with great energy, as though desirous of impressingus with the idea that being among the Happars, we ought to considerourselves perfectly secure.

Although I had some lingering doubts, I feigned great delight with Toby atthis announcement, while my companion broke out into a pantomimicabhorrence of Typee, and immeasurable love for the particular valley inwhich we were; our guides all the while gazing uneasily at one another, asif at a loss to account for our conduct.

They hurried on, and we followed them; until suddenly they set up astrange halloo, which was answered from beyond the grove through which wewere passing, and the next moment we entered upon some open ground, at theextremity of which we descried a long, low hut, and in front of it wereseveral young girls. As soon as they perceived us they fled with wildscreams into the adjoining thickets, like so many startled fawns. A fewmoments after the whole valley resounded with savage outcries, and thenatives came running towards us from every direction.

Had an army of invaders made an irruption into their territory, they couldnot have evinced greater excitement. We were soon completely encircled bya dense throng, and in their eager desire to behold us, they almostarrested our progress; an equal number surrounding our youthful guides,who, with amazing volubility, appeared to be detailing the circumstanceswhich had attended their meeting with us. Every item of intelligenceappeared to redouble the astonishment of the islanders, and they gazed atus with inquiring looks.

At last we reached a large and handsome building of bamboos, and were bysigns told to enter it, the natives opening a lane for us through which topass; on entering, without ceremony we threw our exhausted frames upon themats that covered the floor. In a moment the slight tenement wascompletely full of people, whilst those who were unable to gain admittancegazed at us through its open cane-work.

It was now evening, and by the dim light we could just discern the savagecountenances around us, gleaming with wild curiosity and wonder; the nakedforms and tattooed limbs of brawny warriors, with here and there theslighter figures of young girls, all engaged in a perfect storm ofconversation, of which we were of course the one only theme; whilst ourrecent guides were fully occupied in answering the innumerable questionswhich every one put to them. Nothing can exceed the fierce gesticulationof these people when animated in conversation, and on this occasion theygave loose to all their natural vivacity, shouting and dancing about in amanner that well-nigh intimidated us.

Close to where we lay, squatting upon their haunches, were some eight orten noble-looking chiefs--for such they subsequently proved to be--who, morereserved than the rest, regarded us with a fixed and stern attention,which not a little discomposed our equanimity. One of them in particular,who appeared to be the highest in rank, placed himself directly facing me,looking at me with a rigidity of aspect under which I absolutely quailed.He never once opened his lips, but maintained his severe expression ofcountenance, without turning his face aside for a single moment. Neverbefore had I been subjected to so strange and steady a glance; it revealednothing of the mind of the savage, but it appeared to be reading my own.

WE WERE SOON COMPLETELY ENCIRCLED BY A DENSE THRONG]

After undergoing this scrutiny till I grew absolutely nervous, with a viewof diverting it if possible, and conciliating the good opinion of thewarrior, I took some tobacco from the bosom of my frock, and offered it tohim. He quietly rejected the proffered gift, and, without speaking,motioned me to return it to its place.

In my previous intercourse with the natives of Nukuheva and Tior, I hadfound that the present of a small piece of tobacco would have rendered anyof them devoted to my service. Was this act of the chief a token of hisenmity? Typee or Happar? I asked within myself. I started, for at the samemoment this identical question was asked by the strange being before me. Iturned to Toby; the flickering light of a native taper showed me hiscountenance pale with trepidation at this fatal question. I paused for asecond, and I know not by what impulse it was that I answered, "Typee."The piece of dusky statuary nodded in approval, and then murmured,"Mortarkee?" "Mortarkee," said I, without further hesitation--"Typeemortarkee."

What a transition! The dark figures around us leaped to their feet,clapped their hands in transport, and shouted again and again thetalismanic syllables, the utterance of which appeared to have settledeverything.

When this commotion had a little subsided, the principal chief squattedonce more before me, and throwing himself into a sudden rage, poured fortha string of philippics, which I was at no loss to understand, from thefrequent recurrence of the word Happar, as being directed against thenatives of the adjoining valley. In all these denunciations my companionand I acquiesced, while we extolled the character of the warlike Typees.To be sure our panegyrics were somewhat laconic, consisting in therepetition of that name, united with the potent adjective, "Mortarkee."But this was sufficient, and served to conciliate the good-will of thenatives, with whom our congeniality of sentiment on this point did moretowards inspiring a friendly feeling than anything else that could havehappened.

At last the wrath of the chief evaporated, and in a few moments he was asplacid as ever. Laying his hand upon his breast, he gave me to understandthat his name was "Mehevi," and that, in return, he wished me tocommunicate my appellation. I hesitated for an instant, thinking that itmight be difficult for him to pronounce my real name, and then, with themost praiseworthy intentions, intimated that I was known as "Tom." But Icould not have made a worse selection; the chief could not master it:"Tommo," "Tomma," "Tommee," everything but plain "Tom." As he persisted ingarnishing the word with an additional syllable, I compromised the matterwith him at the word "Tommo"; and by that name I went during the entireperiod of my stay in the valley. The same proceeding was gone through withToby, whose mellifluous appellation was more easily caught.

An exchange of names is equivalent to a ratification of good-will andamity among these simple people; and as we were aware of this fact, wewere delighted that it had taken place on the present occasion.

Reclining upon our mats, we now held a kind of levee, giving audience tosuccessive troops of the natives, who introduced themselves to us bypronouncing their respective names, and retired in high good humour onreceiving ours in return. During the ceremony the greatest merrimentprevailed, nearly every announcement on the part of the islanders beingfollowed by a fresh sally of gaiety, which induced me to believe that someof them at least were innocently diverting the company at our expense, bybestowing upon themselves a string of absurd titles, of the honour ofwhich we were, of course, entirely ignorant.

All this occupied about an hour, when the throng having a littlediminished, I turned to Mehevi, and gave him to understand that we were inneed of food and sleep. Immediately the attentive chief addressed a fewwords to one of the crowd, who disappeared, and returned in a few momentswith a calabash of "poee-poee," and two or three young cocoa-nuts strippedof their husks, and with their shells partly broken. We both of usforthwith placed one of those natural goblets to our lips, and drained itin a moment of the refreshing draught it contained. The poee-poee was thenplaced before us, and even famished as I was, I paused to consider in whatmanner to convey it to my mouth.

This staple article of food among the Marquese islanders is manufacturedfrom the produce of the bread-fruit tree. It somewhat resembles in itsplastic nature our bookbinders' paste, is o

f a yellow colour, and somewhattart to the taste.

Such was the dish, the merits of which I was now eager to discuss. I eyedit wistfully for a moment, and then, unable any longer to stand onceremony, plunged my hand into the yielding mass, and to the boisterousmirth of the natives drew it forth laden with the poee-poee, which adheredin lengthening strings to every finger. So stubborn was its consistency,that in conveying my heavily-freighted hand to my mouth, the connectinglinks almost raised the calabash from the mats on which it had beenplaced. This display of awkwardness--in which, by the bye, Toby kept mecompany--convulsed the bystanders with uncontrollable laughter.

As soon as their merriment had somewhat subsided, Mehevi, motioning us tobe attentive, dipped the fore-finger of his right hand in the dish, andgiving it a rapid and scientific twirl, drew it out coated smoothly withthe preparation. With a second peculiar flourish he prevented thepoee-poee from dropping to the ground as he raised it to his mouth, intowhich the finger was inserted, and was drawn forth perfectly free of anyadhesive matter. This performance was evidently intended for ourinstruction; so I again essayed the feat on the principles inculcated, butwith very ill success.

A starving man, however, little heeds conventional proprieties, especiallyon a South Sea island, and accordingly Toby and I partook of the dishafter our own clumsy fashion, beplastering our faces all over with theglutinous compound, and daubing our hands nearly to the wrist. This kindof food is by no means disagreeable to the palate of a European, though atfirst the mode of eating it may be. For my own part, after the lapse of afew days I became accustomed to its singular flavour, and grew remarkablyfond of it.

So much for the first course; several other dishes followed it, some ofwhich were positively delicious. We concluded our banquet by tossing offthe contents of two more young cocoa-nuts, after which we regaledourselves with the soothing fumes of tobacco, inhaled from a quaintlycarved pipe which passed round the circle.

During the repast, the natives eyed us with intense curiosity, observingour minutest motions, and appearing to discover abundant matter forcomment in the most trifling occurrence. Their surprise mounted thehighest, when we began to remove our uncomfortable garments, which weresaturated with rain. They scanned the whiteness of our limbs, and seemedutterly unable to account for the contrast they presented to the swarthyhue of our faces, embrowned from a six months' exposure to the scorchingsun of the Line. They felt our skin, much in the same way that a silkmercer would handle a remarkably fine piece of satin; and some of themwent so far in their investigation as to apply the olfactory organ.

Their singular behaviour almost led me to imagine that they never beforehad beheld a white man; but a few moments' reflection convinced me thatthis could not have been the case; and a more satisfactory reason fortheir conduct has since suggested itself to my mind.

Deterred by the frightful stories related of its inhabitants, ships neverenter this bay, while their hostile relations with the tribes in theadjoining valleys prevent the Typees from visiting that section of theisland where vessels occasionally lie. At long intervals, however, someintrepid captain will touch on the skirts of the bay, with two or threearmed boats' crews, and accompanied by an interpreter. The natives wholive near the sea descry the strangers long before they reach theirwaters, and aware of the purpose for which they come, proclaim loudly thenews of their approach. By a species of vocal telegraph the intelligencereaches the inmost recesses of the vale in an inconceivably short space oftime, drawing nearly its whole population down to the beach laden withevery variety of fruit. The interpreter, who is invariably a "tabooedKannaka,"(1) leaps ashore with the goods intended for barter, while theboats, with their oars shipped, and every man on his thwart, lie justoutside the surf, heading off from the shore, in readiness at the firstuntoward event to escape to the open sea. As soon as the traffic isconcluded, one of the boats pulls in under cover of the muskets of theothers, the fruit is quickly thrown into her, and the transient visitorsprecipitately retire from what they justly consider so dangerous avicinity.

The intercourse occurring with Europeans being so restricted, no wonderthat the inhabitants of the valley manifested so much curiosity withregard to us, appearing as we did among them under such singularcircumstances. I have no doubt that we were the first white men who everpenetrated thus far back into their territories, or at least the first whohad ever descended from the head of the vale. What had brought us thithermust have appeared a complete mystery to them, and from our ignorance ofthe language it was impossible for us to enlighten them. In answer toinquiries which the eloquence of their gestures enabled us to comprehend,all that we could reply was, that we had come from Nukuheva, a place, beit remembered, with which they were at open war. This intelligenceappeared to affect them with the most lively emotions. "Nukuhevamortarkee?" they asked. Of course we replied most energetically in thenegative.

They then plied us with a thousand questions, of which we could understandnothing more than that they had reference to the recent movements of theFrench, against whom they seemed to cherish the most fierce hatred. Soeager were they to obtain information on this point, that they stillcontinued to propound their queries long after we had shown that we wereutterly unable to answer them. Occasionally we caught some indistinct ideaof their meaning, when we would endeavour by every method in our power tocommunicate the desired intelligence. At such times their gratificationwas boundless, and they would redouble their efforts to make us comprehendthem more perfectly. But all in vain; and in the end they looked at usdespairingly, as if we were the receptacles of invaluable information, buthow to come at it they knew not.

After awhile the group around us gradually dispersed, and we were leftabout midnight (as we conjectured) with those who appeared to be permanentresidents of the house. These individuals now provided us with fresh matsto lie upon, covered us with several folds of tappa, and thenextinguishing the tapers that had been burning, threw themselves downbeside us, and after a little desultory conversation were soon soundasleep.

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale Moby Dick

Moby Dick Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener

Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition)

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition) Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales

Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories

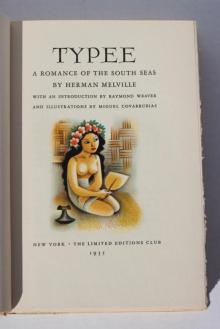

Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories Typee: A Romance of the South Seas

Typee: A Romance of the South Seas Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas

Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War Redburn. His First Voyage

Redburn. His First Voyage Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II

Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II Typee

Typee The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids

The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids Herman Melville- Complete Poems

Herman Melville- Complete Poems Bartleby and Benito Cereno

Bartleby and Benito Cereno Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Mardi and a Voyage Thither

Mardi and a Voyage Thither The Confidence-Man

The Confidence-Man Billy Budd and Other Stories

Billy Budd and Other Stories Bartleby the Scrivener

Bartleby the Scrivener Typee: A Romance of the South Sea

Typee: A Romance of the South Sea I and My Chimney

I and My Chimney Billy Budd

Billy Budd Pierre, Or the Ambiguities

Pierre, Or the Ambiguities Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street

Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street Four Great American Classics

Four Great American Classics White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War The Piazza Tales

The Piazza Tales Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile

Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile