- Home

- Herman Melville

Typee Page 9

Typee Read online

Page 9

CHAPTER VII

The important question, Typee or Happar?--A wild-goose chase--My sufferings--Disheartening situation--A night in the ravine--Morning meal--Happy idea of Toby--Journey towards the valley.

Recovering from my astonishment at the beautiful scene before me, Iquickly awakened Toby, and informed him of the discovery I had made.Together we now repaired to the border of the precipice, and mycompanion's admiration was equal to my own. A little reflection, however,abated our surprise at coming so unexpectedly upon this valley, since thelarge vales of Happar and Typee, lying upon this side of Nukuheva, andextending a considerable distance from the sea towards the interior, mustnecessarily terminate somewhere about this point.

The question now was as to which of those two places we were looking downupon. Toby insisted that it was the abode of the Happars, and I that itwas tenanted by their enemies, the ferocious Typees. To be sure I was notentirely convinced by my own arguments, but Toby's proposition to descendat once into the valley, and partake of the hospitality of its inmates,seemed to me to be risking so much upon the strength of a meresupposition, that I resolved to oppose it until we had more evidence toproceed upon.

The point was one of vital importance, as the natives of Happar were notonly at peace with Nukuheva, but cultivated with its inhabitants the mostfriendly relations, and enjoyed beside a reputation for gentleness andhumanity which led us to expect from them, if not a cordial reception, atleast a shelter during the short period we should remain in theirterritory.

On the other hand, the very name of Typee struck a panic into my heartwhich I did not attempt to disguise. The thought of voluntarily throwingourselves into the hands of these cruel savages, seemed to me an act ofmere madness; and almost equally so the idea of venturing into the valley,uncertain by which of these two tribes it was inhabited. That the vale atour feet was tenanted by one of them, was a point that appeared to us pastall doubt, since we knew that they resided in this quarter, although ourinformation did not enlighten us further.

My companion, however, incapable of resisting the tempting prospect whichthe place held out of an abundant supply of food and other means ofenjoyment, still clung to his own inconsiderate view of the subject, norcould all my reasoning shake it. When I reminded him that it wasimpossible for either of us to know anything with certainty, and when Idealt upon the horrible fate we should encounter were we rashly to descendinto the valley, and discover too late the error we had committed, hereplied by detailing all the evils of our present condition, and thesufferings we must undergo should we continue to remain where we thenwere.

Anxious to draw him away from the subject, if possible--for I saw that itwould be in vain to attempt changing his mind--I directed his attention toa long bright unwooded tract of land which, sweeping down from theelevations in the interior, descended into the valley before us. I thensuggested to him that beyond this ridge might lie a capacious anduntenanted valley, abounding with all manner of delicious fruits; for Ihad heard that there were several such upon the island, and proposed thatwe should endeavour to reach it, and if we found our expectations realizedwe should at once take refuge in it and remain there as long as wepleased.

He acquiesced in the suggestion; and we immediately, therefore, begansurveying the country lying before us, with a view of determining upon thebest route for us to pursue; but it presented little choice, the wholeinterval being broken into steep ridges, divided by dark ravines,extending in parallel lines at right angles to our direct course. Allthese we would be obliged to cross before we could hope to arrive at ourdestination.

A weary journey! But we decided to undertake it, though, for my own part,I felt little prepared to encounter its fatigues, shivering and burning byturns with the ague and fever; for I know not how else to describe thealternate sensations I experienced, and suffering not a little from thelameness which afflicted me. Added to this was the faintness consequent onour meagre diet--a calamity in which Toby participated to the same extentas myself.

These circumstances, however, only augmented my anxiety to reach a placewhich promised us plenty and repose, before I should be reduced to a statewhich would render me altogether unable to perform the journey.Accordingly we now commenced it by descending the almost perpendicularside of a steep and narrow gorge, bristling with a thick growth of reeds.Here there was but one mode for us to adopt. We seated ourselves upon theground, and guided our descent by catching at the canes in our path. Thevelocity with which we thus slid down the side of the ravine soon broughtus to a point where we could use our feet, and in a short time we arrivedat the edge of the torrent, which rolled impetuously along the bed of thechasm.

After taking a refreshing draught from the water of the stream, weaddressed ourselves to a much more difficult undertaking than the last.Every foot of our late descent had to be regained in ascending theopposite side of the gorge--an operation rendered the less agreeable fromthe consideration that in these perpendicular episodes we did not progressa hundred yards on our journey. But, ungrateful as the task was, we setabout it with exemplary patience, and after a snail-like progress of anhour or more, had scaled perhaps one half of the distance, when the feverwhich had left me for awhile returned with such violence, and accompaniedby so raging a thirst, that it required all the entreaties of Toby toprevent me from losing all the fruits of my late exertion, byprecipitating myself madly down the cliffs we had just climbed, in questof the water which flowed so temptingly at their base. At the moment allmy hopes and fears appeared to be merged in this one desire, careless ofthe consequences that might result from its gratification. I am aware ofno feeling, either of pleasure or of pain, that so completely deprives oneof all power to resist its impulses, as this same raging thirst.

Toby earnestly conjured me to continue the ascent, assuring me that alittle more exertion would bring us to the summit, and that then in lessthan five minutes we should find ourselves at the brink of the stream,which must necessarily flow on the other side of the ridge.

"Do not," he exclaimed, "turn back, now that we have proceeded thus far;for I tell you that neither of us will have the courage to repeat theattempt, if once more we find ourselves looking up to where we now arefrom the bottom of these rocks!"

I was not yet so perfectly beside myself as to be heedless of theserepresentations, and therefore toiled on, ineffectually endeavouring toappease the thirst which consumed me, by thinking that in a short time Ishould be able to gratify it to my heart's content.

At last we gained the top of the second elevation, the loftiest of those Ihave described as extending in parallel lines between us and the valley wedesired to reach. It commanded a view of the whole intervening distance;and, discouraged as I was by other circumstances, this prospect plunged meinto the very depths of despair. Nothing but dark and fearful chasms,separated by sharp crested and perpendicular ridges as far as the eyecould reach. Could we have stepped from summit to summit of these steepbut narrow elevations we could easily have accomplished the distance; butwe must penetrate to the bottom of every yawning gulf, and scale insuccession every one of the eminences before us. Even Toby, although notsuffering as I did, was not proof against the disheartening influences ofthe sight.

But we did not long stand to contemplate it, impatient as I was to reachthe waters of the torrent which flowed beneath us. With an insensibilityto danger which I cannot call to mind without shuddering, we threwourselves down the depths of the ravine, startling its savage solitudeswith the echoes produced by the falling fragments of rock we every momentdislodged from their places, careless of the insecurity of our footing,and reckless whether the slight roots and twigs we clutched at sustainedus for the while, or treacherously yielded to our grasp. For my own part,I scarcely knew whether I was helplessly falling from the heights above,or whether the fearful rapidity with which I descended was an act of myown volition.

AT LAST WE GAINED THE TOP OF THE SECOND ELEVATION]

In

a few minutes we reached the foot of the gorge, and kneeling upon asmall ledge of dripping rocks, I bent over to the stream. What a delicioussensation was I now to experience! I paused for a second to concentrateall my capabilities of enjoyment, and then immerged my lips in the clearelement before me. Had the apples of Sodom turned to ashes in my mouth, Icould not have felt a more startling revulsion. A single drop of the coldfluid seemed to freeze every drop of blood in my body; the fever that hadbeen burning in my veins gave place on the instant to death-like chills,which shook me one after another like so many shocks of electricity, whilethe perspiration produced by my late violent exertions congealed in icybeads upon my forehead. My thirst was gone, and I fairly loathed thewater. Starting to my feet, the sight of those dank rocks, oozing forthmoisture at every crevice, and the dark stream shooting along its dismalchannel, sent fresh chills through my shivering frame, and I felt asuncontrollable a desire to climb up towards the genial sunlight as Ibefore had to descend the ravine.

After two hours' perilous exertions we stood upon the summit of anotherridge, and it was with difficulty I could bring myself to believe that wehad ever penetrated the black and yawning chasm which then gaped at ourfeet. Again we gazed upon the prospect which the height commanded, but itwas just as depressing as the one which had before met our eyes. I nowfelt that in our present situation it was in vain for us to think of everovercoming the obstacles in our way, and I gave up all thoughts ofreaching the vale which lay beyond this series of impediments; while atthe same time I could not devise any scheme to extricate ourselves fromthe difficulties in which we were involved.

The remotest idea of returning to Nukuheva unless assured of our vessel'sdeparture, never once entered my mind, and indeed it was questionablewhether we could have succeeded in reaching it, divided as we were fromthe bay by a distance we could not compute, and perplexed too in ourremembrance of localities by our recent wanderings. Besides, it wasunendurable the thought of retracing our steps and rendering all ourpainful exertions of no avail.

There is scarcely anything when a man is in difficulties that he is moredisposed to look upon with abhorrence than a right-about retrogrademovement--a systematic going over of the already trodden ground: andespecially if he has a love of adventure, such a course appearsindescribably repulsive, so long as there remains the least hope to bederived from braving untried difficulties.

It was this feeling that prompted us to descend the opposite side of theelevation we had just scaled, although with what definite object in viewit would have been impossible for either of us to tell.

Without exchanging a syllable upon the subject, Toby and myselfsimultaneously renounced the design which had lured us thus far--perceivingin each other's countenances that desponding expression which speaks moreeloquently than words.

Together we stood towards the close of this weary day in the cavity of thethird gorge we had entered, wholly incapacitated for any further exertion,until restored to some degree of strength by food and repose.

We seated ourselves upon the least uncomfortable spot we could select, andToby produced from the bosom of his frock the sacred package. In silencewe partook of the small morsel of refreshment that had been left from themorning's repast, and without once proposing to violate the sanctity ofour engagement with respect to the remainder, we rose to our feet, andproceeded to construct some sort of shelter under which we might obtainthe sleep we so greatly needed.

Fortunately the spot was better adapted to our purpose than the one inwhich we had passed the last wretched night. We cleared away the tallreeds from a small but almost level bit of ground, and twisted them into alow basket-like hut, which we covered with a profusion of long thickleaves, gathered from a tree near at hand. We disposed them thickly allaround, reserving only a slight opening that barely permitted us to crawlunder the shelter we had thus obtained.

These deep recesses, though protected from the winds that assail thesummits of their lofty sides, are damp and chill to a degree that onewould hardly anticipate in such a climate; and being unprovided withanything but our woollen frocks and thin duck trousers to resist the coldof the place, we were the more solicitous to render our habitation for thenight as comfortable as we could. Accordingly, in addition to what we hadalready done, we plucked down all the leaves within our reach and threwthem in a heap over our little hut, into which we now crept, raking afterus a reserved supply to form our couch.

That night nothing but the pain I suffered prevented me from sleeping mostrefreshingly. As it was, I caught two or three naps, while Toby slept awayat my side as soundly as though he had been sandwiched between two Hollandsheets. Luckily it did not rain, and we were preserved from the miserywhich a heavy shower would have occasioned us.

In the morning I was awakened by the sonorous voice of my companionringing in my ears and bidding me rise. I crawled out from our heap ofleaves, and was astonished at the change which a good night's rest hadwrought in his appearance. He was as blithe and joyous as a young bird,and was staying the keenness of his morning's appetite by chewing the softbark of a delicate branch he held in his hand, and he recommended the liketo me, as an admirable antidote against the gnawings of hunger.

For my own part, though feeling materially better than I had done thepreceding evening, I could not look at the limb that had pained me soviolently at intervals during the last twenty-four hours, withoutexperiencing a sense of alarm that I strove in vain to shake off.Unwilling to disturb the flow of my comrade's spirits, I managed to stiflethe complaints to which I might otherwise have given vent, and callingupon him good-humouredly to speed our banquet, I prepared myself for it bywashing in the stream. This operation concluded, we swallowed, or ratherabsorbed, by a peculiar kind of slow sucking process, our respectivemorsels of nourishment, and then entered into a discussion as to the stepsit was necessary for us to pursue.

"What's to be done now?" inquired I, rather dolefully.

"Descend into that same valley we descried yesterday," rejoined Toby, witha rapidity and loudness of utterance that almost led me to suspect he hadbeen slyly devouring the broadside of an ox in some of the adjoiningthickets. "What else," he continued, "remains for us to do but that, to besure? Why, we shall both starve, to a certainty, if we remain here; and asto your fears of those Typees--depend upon it, it is all nonsense. It isimpossible that the inhabitants of such a lovely place as we saw can beanything else but good fellows; and if you choose rather to perish withhunger in one of these soppy caverns, I for one prefer to chance a bolddescent into the valley, and risk the consequences."

"And who is to pilot us thither," I asked, "even if we should decide uponthe measure you propose? Are we to go again up and down those precipicesthat we crossed yesterday, until we reach the place we started from, andthen take a flying leap from the cliffs to the valley?"

"'Faith, I didn't think of that," said Toby; "sure enough, both sides ofthe valley appeared to be hemmed in by precipices, didn't they?"

"Yes," answered I; "as steep as the sides of a line-of-battle ship, andabout a hundred times as high." My companion sank his head upon hisbreast, and remained for awhile in deep thought. Suddenly he sprang to hisfeet, while his eyes lighted up with that gleam of intelligence that marksthe presence of some bright idea.

"Yes, yes," he exclaimed; "the streams all run in the same direction, andmust necessarily flow into the valley before they reach the sea; all wehave to do is just to follow this stream, and sooner or later, it willlead us into the vale."

"You are right, Toby," I exclaimed, "you are right; it must conduct usthither, and quickly too; for, see with what a steep inclination the waterdescends."

"It does, indeed," burst forth my companion, overjoyed at my verificationof his theory, "it does, indeed; why, it is as plain as a pike-staff. Letus proceed at once; come, throw away all those stupid ideas about theTypees, and hurrah for the lovely valley of the Happars!"

"You will have it to be Happar, I see, my dear fellow; pray Heaven, youmay not find yourse

lf deceived," observed I, with a shake of my head.

"Amen to all that, and much more," shouted Toby, rushing forward; "butHappar it is, for nothing else than Happar can it be. So glorious avalley--such forests of bread-fruit trees--such groves of cocoa-nut--suchwildernesses of guava-bushes! Ah, shipmate! don't linger behind: in thename of all delightful fruits, I am dying to be at them. Come on, come on;shove ahead, there's a lively lad; never mind the rocks; kick them out ofthe way, as I do; and to-morrow, old fellow, take my word for it, we shallbe in clover. Come on"; and so saying, he dashed along the ravine like amadman, forgetting my inability to keep up with him. In a few minutes,however, the exuberance of his spirits abated, and, pausing for awhile, hepermitted me to overtake him.

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale

Moby Dick; Or, The Whale Moby Dick

Moby Dick Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener

Benito Cereno and Bartleby the Scrivener Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition)

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (Annotated Edition) Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales

Billy Budd and the Piazza Tales Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories

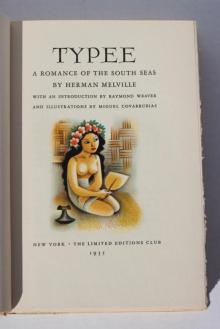

Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories Typee: A Romance of the South Seas

Typee: A Romance of the South Seas Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas

Omoo: Adventures in the South Seas White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War

White Jacket; Or, The World on a Man-of-War Redburn. His First Voyage

Redburn. His First Voyage Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II

Mardi: and A Voyage Thither, Vol. II Typee

Typee The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids

The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids Herman Melville- Complete Poems

Herman Melville- Complete Poems Bartleby and Benito Cereno

Bartleby and Benito Cereno Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Moby-Dick (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Mardi and a Voyage Thither

Mardi and a Voyage Thither The Confidence-Man

The Confidence-Man Billy Budd and Other Stories

Billy Budd and Other Stories Bartleby the Scrivener

Bartleby the Scrivener Typee: A Romance of the South Sea

Typee: A Romance of the South Sea I and My Chimney

I and My Chimney Billy Budd

Billy Budd Pierre, Or the Ambiguities

Pierre, Or the Ambiguities Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street

Bartleby, The Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street Four Great American Classics

Four Great American Classics White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War

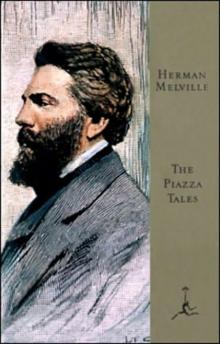

White Jacket or, The World on a Man-of-War The Piazza Tales

The Piazza Tales Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile

Israel Potter. Fifty Years of Exile